We need to do 10x more in 2025

Capacity-building for the post-IRA electrification push.

Fifteen years ago I first joined the Obama campaign as a volunteer, but within a few days I was ready to quit my comfy job and move across the country to join as a full-time staffer. I was attending an organizing training led by Marshall Ganz, a former United Farmworkers Organizer and advisor to Cesar Chavez turned Harvard professor, and while I was already a huge fan of Barack Obama, what flipped me from “wanting to help” to essentially leaving my life behind wasn’t Obama’s stirring speeches or his vision for the country, it was learning about the campaign’s strategy and my place in it.

We wouldn’t beat them with ads or money. We didn’t have experienced campaign staff (they all worked for the other candidates). We needed to build the largest army of community organizers the country had ever seen, and win votes one relationship at a time. Marshall weaved an inspiring and compelling narrative that tied this strategy to his personal story, Barack Obama’s story, the story of the entire country, and to that particular moment in history that called us to act. I was so fired up!

Then Marshall announced our first big, official campaign objective: to recruit supporters to host “BBQs for Barack.”

What?

I was deeply confused. This was exactly the kind of wheel-spinning, navel-gazing stuff that made me wary of political activism to begin with. But as it turned out, it was a brilliant and important tactic in those early days. I later learned that events like these were ideal first-steps toward recruiting organizers because 1)if you just say “we need organizers who want to lead the largest organizing effort our country has ever seen”, the kinds of people who are likely to raise their hands are actually not the people you want, 2) it was too early in the election cycle to have people doing typical campaign activities like canvassing door to door or making phone calls, and 3) the BBQs served as a test of the host’s organizing ability. Well-attended events required careful planning and strategy, a strong existing network or community, the ability to reach and motivate people to take action, and making and keeping commitments to others.

In 2007, we were not building a movement to change the country, we were building the capacity to build that movement in 2008.

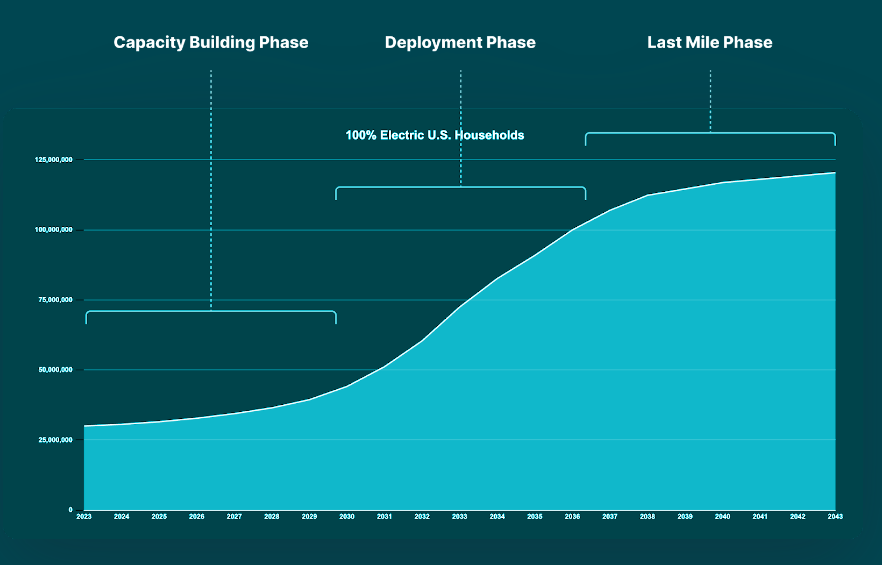

I share that anecdote because it’s clear to me now that we are very much in the capacity-building phase of the movement to electrify everything in this country. And I’m not sure we understand and appreciate that as much as we probably should - me included! I catch myself saying things like, “one biillion machines, so 50 Million per year over the next 20 years,” when I know we won’t be deploying close to 50M this year, next year, or the year after. So when you actually look at what it will take to decarbonize the economy in the next ~20 years, you realize that the task in front of us requires dramatically increasing our capacity in the years ahead. (A related phenomenon that also comes into play here is the fact that the last 10% of the work is going to be 100x harder and more stubborn than the rest, so our window to get the bulk of the work done lies in those critical middle years.)

I’m certainly no economist, but it’s intuitive to me that increasing capacity usually involves trade-offs with current production. We can’t deploy 100% of our resources and labor towards installing as many heat pumps as possible this year and build the capacity to install 10x more in 2025. Right?

Fig 1: Chart showing likely U.S. household electrification adoption curve.

Anyhow, for my part I am focusing on a project aimed at building a key piece of missing digital infrastructure for residential electrification (more on that soon!), and in order to clearly illustrate this concept for the folks I’m working with, I came up with a crude chart (Fig 1), showing what the adoption curve toward electrifying the rest of America’s 120M households might look like. I may be off by millions of homes or a few years in either direction, but the takeaway is the same: if you want to electrify every home in the U.S. over the next 20 years, and you account for the years it will take to build capacity, as well as the fact that the last ~10% of homes are going to be incredibly difficult, you end up with a period of time that is much less than 20 years during which we will need to do the vast majority of the work.

Capacity-building in the climate space takes many forms, of course, from modernizing the grid to building new battery factories, or training new workforces. I know there’s great work happening on all these fronts, all over the world. Whatever it is we’re working on, it just seems important to keep this capacity-building framework in mind, to always remember that our work today must build toward a future where can do 10x more of it in just a few years. In my experience, sometimes that means investing in strategies that might seem less impactful at first. It also requires rethinking how we measure our impact (e.g. direct GHG reductions vs. added future GHG reduction capacity).

We humans are heavily biased towards the present. We inherently value the impact we can see now more than the impact we might create in the future. To me this feels like a force of nature I have to constantly push back on in my own work. Maybe I’ll put this chart on the wall above my desk.

I’d love to hear from you! What does capacity-building look like in your climate work?

Climate incentive programs have an infrastructure problem.

The IRA is our golden opportunity to meet the challenge of the climate crisis - but success will require a rapid, coordinated effort to build new digital and human infrastructure.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is a huge victory for the climate movement, for U.S. households, and for humanity. It’s not perfect, but it is the biggest climate policy win in my lifetime, and I have relished the infusion of joy, determination, and hope the IRA has brought to virtually every corner of the movement. I’m now starting to dig deeper into the implications of the IRA for the work I know best: the marketing, outreach, and education efforts required to deploy clean technology equitably and at the scale of the problem. And, well… hoo boy, we’ve got some things to figure out!

I spent the last seven years as Vice President of Outreach at GRID Alternatives. As the administrator of the biggest and most successful climate equity incentive programs in the U.S., GRID has been at the leading edge of implementing the types of programs contained in the IRA for almost two decades. My brilliant former colleagues working on program administration, construction, technical assistance, clean mobility, and workforce development will be critical sources of knowledge and best practices as this work grows exponentially over the next few years. For my part, I hope sharing what I’ve learned bringing these programs to scale in places like California can help illuminate some obstacles that could prevent us from realizing the potential of the IRA.

To begin with, I want to share some of the biggest and most urgent consumer education and marketing challenges (and opportunities) I see ahead of us. Of course, there’s a long list of other critical and related issues, from supply chain and manufacturing bottlenecks, to contractor outreach and education. But in my view, our solutions to all of these problems should be designed with the consumer experience in mind from the outset, so that’s where I’ll begin.

Here’s an incomplete list of what’s been bouncing around in my head since that fateful moment in July when the New York Times alert hit my phone:

“In stunning reversal, Joe Manchin signals support for climate bill.”

It’s too hard to do the right thing.

This is the big, underlying consumer problem we all need to solve. The process of electrifying our lives is a daunting journey for consumers, requiring complex math, navigating bureaucracies, finding and coordinating multiple contractors, successfully applying for financing, and more. Even simply figuring out what choices are available for your household is complicated. And these challenges are just the baseline - for folks living in the disadvantaged and historically under-resourced communities most impacted by climate change and pollution, the list of barriers is much longer.

Simply making things cheaper and affordable is not nearly enough, as evidenced by the fact that programs like DAC-SASH in California, which provides rooftop solar to low-income homeowners for no cost, require marketing and outreach efforts similar in scale and cost to those of for-profit solar installers.

Thankfully, there is now a sizable and growing group of organizations working across the public and private sectors to reduce these barriers and streamline access to climate benefits. But as I’ve learned in helping to lead one such effort with Access Clean CA, there are underlying structural and systemic challenges that we need to address at the national level, as a movement, to make electrification easier and more equitable.

Without a broad, comprehensive, and coordinated “wartime” effort to address these challenges, I believe we will fail to realize the transformative potential of the IRA and lose critical years in the race to decarbonize in time.

Digital Infrastructure

Buying a heat pump should be easier than buying a home.

Even when we walk into a store, call a local business on a landline, or talk to someone on our front doorstep, our experience as consumers is facilitated by digital infrastructure. From data and targeting, marketing and ad tech, to point-of-sale and customer relationship management software, nearly every transaction and decision we make as consumers these days relies on digital infrastructure. We have come to expect frictionless experiences, even for major purchases and highly complex transactions like buying a home. And while much of this infrastructure is invisible to the average consumer, it has been grown over decades of innovation and through billions of dollars of investment.

We do not have the digital infrastructure we need to electrify 120 Million+ households in the U.S., and we simply don’t have time to just let the market do its thing and wait for that infrastructure to grow organically.

Inserting incentives and rebates - and in many cases, multiple rebates and incentives for a single product or project - into these already complex customer journeys creates friction, confusion, and sometimes full-on chaos. This makes it difficult if not impossible (and very costly) to conduct effective marketing, education, and outreach for these programs. Don’t take my word for it; just stop what you’re doing and take a few minutes to try and figure out which incentive programs are available to you, what it takes to qualify, how much money you can save by participating, and how to take action. It’s already a mess, and it is going to get much much worse as federal dollars start flowing if we don’t act swiftly and collaboratively to address this.

We’re not starting from scratch, of course, but with the passage of the IRA, we need to invest in a new layer of digital infrastructure to incorporate incentive programs in ways that simplify and streamline the consumer electrification experience. There are some promising startups popping up to address some of the gaps here, but I’m concerned that a purely market-based approach to solving this problem will take too long and produce a fragmented landscape that creates problems of its own. Instead, we need to encourage and fund innovation, while simultaneously facilitating and incentivizing an unprecedented level of collaboration, transparency, and cooperation amongst the investors, startups, and big tech companies working on this problem.

Some ideas:

An “Incentive Infrastructure Collaborative” that helps define and evangelize standards and data structures that enable interoperability among products that leverage, provide access to, and/or educate consumers about climate incentives. We’ve made some early steps in this direction in California, and I would love to help make this happen on a much bigger scale. It’s essential. Who’s in?

An API for climate incentives that aggregates not only federal/IRA incentive data but also state, local, and utility programs. This should be free to use for any non-profit or government agency doing marketing and outreach to disadvantaged communities and could be sustainably funded by revenue from OEMs, retailers, and other commercial uses. The biggest challenge here is making the data actionable - going beyond a simple directory of programs and incentive amounts and including detailed program data that is updated regularly and supports use-cases like building savings calculators, determining likely program eligibility, and displaying how multiple incentives can “stack” to produce even greater savings. As it happens, I’ve been working with a crack team of engineers on an MVP for this and we’re exploring ways to fund and support scaling it nationally. If you are interested in getting involved, drop me a line!

Big tech companies should take an approach similar to their work on elections, natural disasters, and the COVID 19 pandemic, and invest in tools and features that leverage their vast resources and share of attention to help consumers navigate the electrification journey. I’ve got ideas, but I imagine hundreds if not thousands of employees at these companies have much better ones. Whatup FAANGers?

Open Source Everything. While we don’t need every tech company in the space to give away their core IP, a true “wartime effort” to address these challenges should include an unprecedented amount of transparency and collaboration amongst product folks, designers, engineers, marketers, and operators. We need every possible advantage we can get in this fight, and there’s undoubtedly thousands of people out there reinventing the wheel over and over again as we speak. How can we fix that?

Open-source whenever possible.

Build and share things like micro services, UI component libraries and other internal tools that might help other teams move faster.

Create a massive shared repository of non-branded marketing collateral (how many different “how heat pumps work” graphics does the world really need?)

Share your coolest operations and finance templates in Excel, Google Docs, Airtable, etc.

Fund this stuff! We need an infusion of capital to fund these efforts, and we need it fast. Tech infrastructure might not be the sexiest investment with the biggest returns (though a few early Twilio investors will beg to differ), but investors who are pouring money into climate tech startups expecting to benefit from IRA incentive programs should view an investment in this digital infrastructure as a substantial multiplier, if not an essential catalyst for achieving scale in this space. We need an all-of-the-above approach to capitalizing this work, combining VC-backed innovation with grant funding, program admin funding, and other non-dilutive sources of capital when appropriate. And for the record, I do believe there are plenty of opportunities to build fast-growing, profitable businesses that meet some of these needs.

Human Infrastructure

The enormous marketing, outreach, and education effort required to implement the IRA over the next decade is not going to be a top-down, centralized effort. It’s not even going to be 50 different state efforts. It’s going to require the simultaneous mobilization of thousands of organizations across the country, using existing networks and coalitions as well as building new ones. Coordination will be extremely difficult, but absolutely essential if we are to succeed.

The key to success, in my opinion, is to reimagine the role of government and other large institutional players to include funding the resources, infrastructure, and tools these organizations will need to collaborate effectively, and acting as facilitators of that collaboration. In addition to some of the technology I’ve mentioned above, this should also include supporting the human beings we are relying on to carry out this work.

A few things I’ve learned on this topic:

Community Based Organizations (CBOs) play an essential role in any effort to bring clean technologies to disadvantaged and low-income communities, primarily because by far the biggest barrier we face in these communities is a lack of trust. Trust in government. Trust that anything in life is truly free. And to be very frank, trust in white people working for big nonprofits. CBOs are not just a channel for reaching consumers, they are a vital source of truth and information about community needs and desires. We need to engage with CBOs as key partners in developing our solutions, not just as channels for selling them. Thankfully, this need has been fairly well articulated in the IRA and in state legislation and regulation in places like CA, and we now have a mandate to work with CBOs around the country.

CBOs need capacity-building funds and training, not just money to conduct outreach. For Access Clean CA, we built a vast outreach network consisting of CBOs, tribal governments, labor unions, and Program Administrators from every corner of the state. Larger partners like labor unions were generally able to take things like marketing collateral, talking points, and digital tools and easily plug them into their professionalized organizing and marketing operations. But most CBOs engage in a wide range of community-based work, and if they have full-time staff at all, they are most often generalists. It is not enough to build outreach programs that spend heavily on creative/content development, direct marketing, and paid media, then use CBO funds to simply pay people to hand out flyers, post on Facebook, and attend events. CBOs need funding and training to build their internal capacity to expand their work. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to this; it takes a concerted effort to engage with - and listen to - individual CBOs to understand their unique strengths as well as gaps in capacity.

ME&O Workforce Development. With the passage of the IRA, we are finally set to invest heavily in workforce development to ensure we have the electricians, engineers, and other skilled laborers we need to build a better future for our country. But based on what I’ve seen in California, we are dramatically underestimating the workforce we will need to bring these technologies to consumers, especially in disadvantaged communities, communities of color, and tribal communities. Being effective at this work requires just as much skill as installing a heat pump or solar panels - just ask anyone in solar sales how easy their job is. Where will all of these people come from? How will they be trained? These are career pathways that have considerable earning potential (or at least, they should - see my next point) and importantly, these jobs may appeal to people with very different aptitudes and interests than those seeking jobs in construction, engineering, etc. And while they require skill, training, and practice, they usually don’t require the additional burden of prerequisites like higher education or certifications. We should be investing in creating on-ramps to this additional, complimentary career pathway for young people, people of color, and mid-career professionals looking to contribute to the cause.

Fair Pay. Historically, government-funded climate benefit programs have not invested enough in outreach and education, nor in the staffing required to succeed in this work. My personal opinion is that most people who haven’t done this work - which includes most policymakers as well as most climate policy advocates - assume that essentially “giving away money” should be easy and relatively low-cost. It’s not. That leaves organizations tasked with implementing these programs with insufficient outreach budgets, straining to meet enrollment goals, and unable to recruit and retain staff who have the resources to be successful. It’s pennywise and pound foolish. And the equity implications of this are profound and disheartening. Incentive programs that are under-resourced in these areas inevitably end up distributing benefits to the households that are the easiest to reach and have the fewest barriers to participating. If we are serious about equity and climate justice, we need to put our money where our mouth is and recalibrate our investments in ME&O staffing to reflect that. Whether it is canvassers going door-to-door in disadvantaged communities, or graphic designers, content marketers, and social media managers working for nonprofits and government agencies - the people doing this work should be paid market wages and treated like the highly skilled and essential professionals they are.

Thoughts?

What am I missing? Who is already working on some of these problems that I’m not aware of? Want to talk through an idea you have, or a problem your organization is facing? Want to work together on something? I’m doing more reading and listening than talking at the moment, and I’d love to hear from you!

Drop me a line: jeff@billionmachines.com